Minidoka Relocation Center National Monument -- A

relocation center for Japanese-American citizens detained during World

War II.

June 5, 2007.

We are staying at High

Adventure River Tours RV-Park/Store & Dutch Oven Cafe

located on the southeast corner of exit 147 near Hagerman,

Idaho. It is a nice RV-Park with shade and long pull-through

sites. PPA with tax ran

$16 for FHU.

For those of you that are not familiar with PPA

(Pass Port America) it

is an organization you can join for less than $50 per-year. Campgrounds

that belong to PPA offer

1/2 price discounts. That kind of savings can quickly add up. While

participating PPA parks

generally have some restrictions on dates the PPA

offer is valid, or possibly days of the week the discount is valid,

or perhaps the number of days that the PPA

discount will be honored the discount is genuine. Many times PPA

campgrounds are new campgrounds that need help in getting established.

Other times PPA campgrounds

may be on the outskirts of town instead of in the "prime"

location thus they need to provide an incentive for campers to stay

with them. Whatever the reason PPA

campgrounds generally provide a much cheaper option. PPA

is the only campground organization that I think is worth the cost.

PPA does not have a

gimic. What you see is what you get. Once you join they send you a

directory listing all participating campgrounds. The PPA

directory is the FIRST directory we check when trying to locate

a place to spend the night. You can join PPA

by calling 228-452-9972. If you decide to join PPA,

it would be nice if you gave them my number "R-0156251"

as the PPA member that

told you about PPA. In

return PPA will give

me a years membership free. I will thank you in advance for that kindness.

Thank you.

One

day last week we visited the Minidoka Internment National Monument.

At least at that time we thought it was supposed to be a National

Monument. We were a bit puzzled upon arrival at the site since it

didn't look like any National Monument we have ever visited. There

was nothing, absolutely NOTHING, that identified the place as a National

Monument or even that it was the remnants of the Minidoka

Internment site. There were no roadside signs directing us

to this National Monument.

Now we know more about it and why it looked the way it did since

we stopped by the Hagerman

Fossil Beds National Monument Visitor Center in Hagerman.

While viewing fossil information we noticed an exhibit about the Minidoka

Internment National Monument. Being inquisitive I started

asking questions. The answers to those questions were revealing. It

seems that Bill Clinton, when he was President, established the Minidoka

Internment National Monument by Presidential proclamation

on January 17, 2001. That is the way National Monuments are established.

However, it is up to congress to fund National Monuments. Since 2001

the U.S. Department of the Interior, (National Park Service) has developed

a "plan" on how to develop the monument and is presenting

it to congress this year. It will either be funded or not funded.

I think I recall that the National Park Service has presented the

"plan" previously but that congress did not fund the "plan".

I also think that the park ranger who was providing me with this info

said that if it wasn't funded this year the plan would probably be

shelved for 10 to 20 years before being presented again.

Now I understand why it is a "National Monument" but does

not look like a normal National Monument --- it has not been funded.

In the process of developing this proposed Management Plan that is

being presented to congress the National Park Service has collected

documents and memorabilia, some of which, was on display in the Hagerman

Fossil Beds National Monument Visitor Center.

I am going to share some of that information with you.

In some places the Center is referred to as a "relocation center"

while in others it is referred to as an "Internment Center".

It seems to me like someone is searching for a politically correct

word that "sounds not so harsh" if you will. Words such

as evacuation, exclusion, detention, incarceration, internment, and

relocation have been used to describe the event of forcefully removing

people from their homes and communities. The people themselves have

been referred to with words such as evacuees, detainees, inmates,

internees, nonaliens, and prisoners. Also, the people have been referred

to as Japanese, Japanese Americans, Japanese legal resident aliens,

Nikkea, and by their generation in the United States -- Issei (first

generation) and Nisei (second generation). Finally, the facilities

used to implement the policy have been called assembly centers, camps,

concentration camps, incarceration camps, internment camps, prisons,

relocation centers, and War Relocation Centers.

Now I think I understand why funding for this National Monument may

be having difficulty sliding through congress. These terms are politically

charged. There is something there to offend almost everyone. I wonder

if this has anything to do with the funding issue?

Now lets look at what led up to this "Internment Center"

for lack of a better term.

In the 1800's times were hard in Japan and many emigrants from agricultural

and fishing villages in Western Japan crossed the Pacific Ocean to

seek economic opportunity in America.

While most families originally intended to return to their birthplace,

they established farms, businesses, and communities. America became

their new home.

Japanese immigrants arriving the the US

Arriving in a new country searching for economic opportunity.

Even back in the 1800s anti-Japanese movements arose from existing

anti-Asian prejudices. The rise of militarism in Japan had newspapers

fanning the flames of prejudice, warning of the "yellow peril."

The Issei (1st generation) and Nisei (2nd generation) encountered

various forms of racial prejudice in the United States. The fourteenth

Amendment (1868) was passed to permit the naturalization of "white

people" and "aliens of African descent" only and restricted

the flow of new arrivals through quotas. Congress passed laws that

prohibited resident aliens from owning land. The Immigration Act of

1924 prohibited all further Japanese immigration.

Businesses were built; families grew and celebrated their heritage

despite the added hardships and attitudes of prejudice.

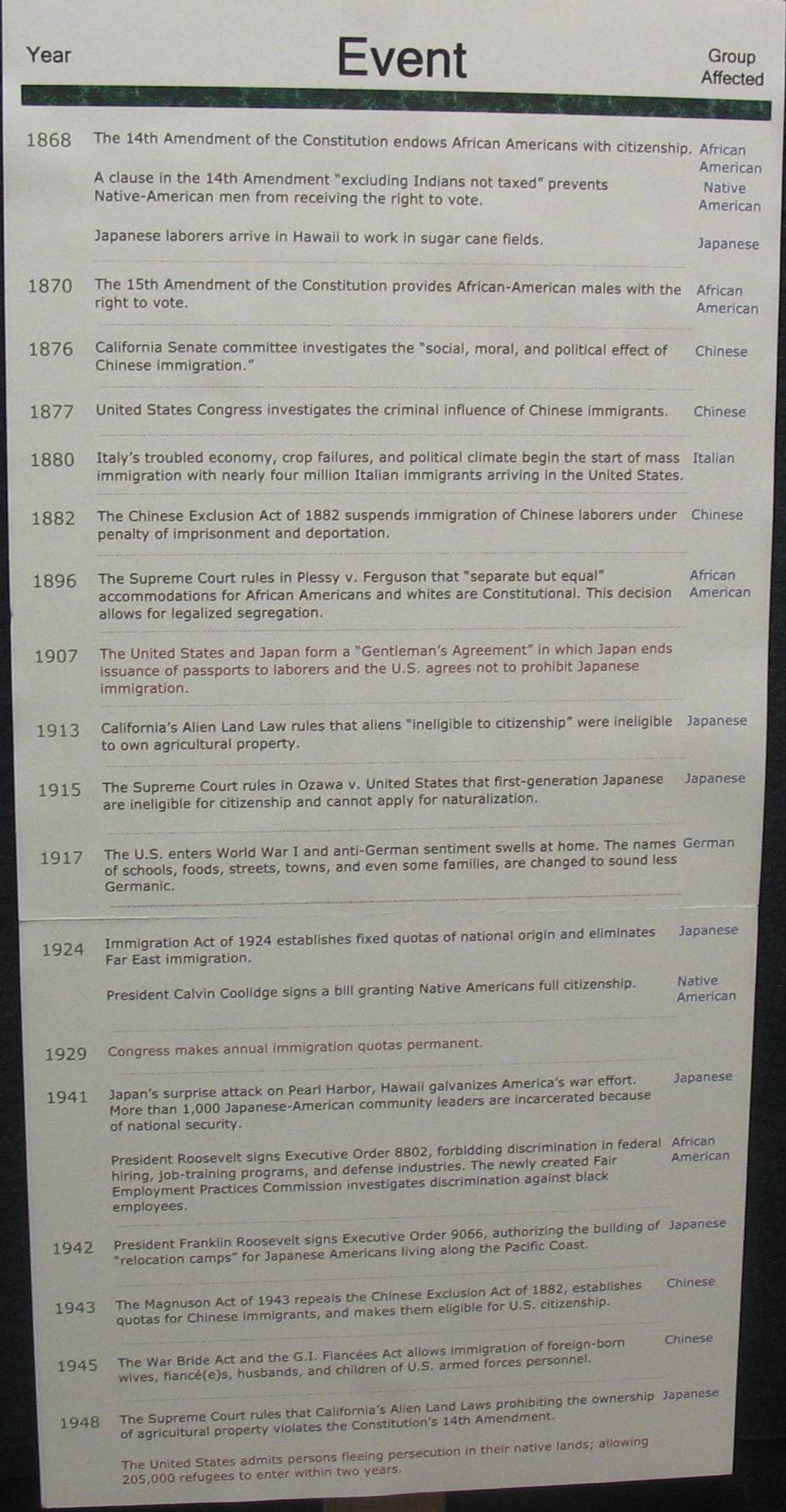

List of Laws & Amendments that deal with prejudice

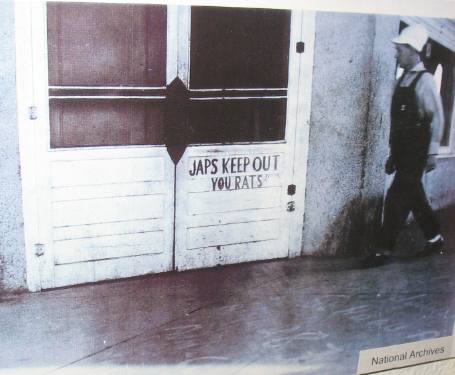

Japs Keep Moving - White Man's Neighborhood

Japs Keep Out

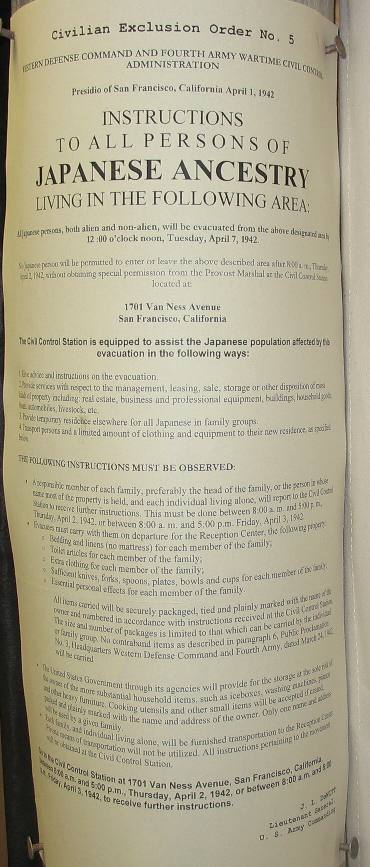

Executive Order 9066

Then on February 19, 1942, as wartime hysteria mounted, President

Roosevelt signed

Executive Order 9066.

This authorized the U.S. military to remove "any and all persons"

from designated areas on the West Coast.

However, the order specifically targeted people with 1/16th or more

of Japanese blood including Japanese Americans and resident aliens.

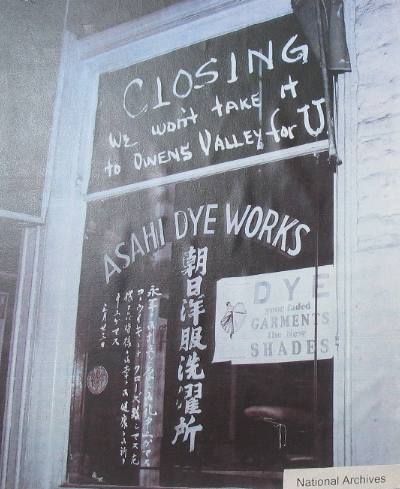

With as little as one week to one day's notice, nearly 120,00 Nikkei

(1st generation) living within designated areas had to abandon their

homes and livelihoods. Most sold off their assets at a fraction of

their worth. Some entrusted property to friends and neighbors. They

were permitted to take "only what they could carry," assigned

a number, tagged, and escorted by armed Military Police to one of

fifteen temporary assembly centers. Families were occasionally separated.

Assembly centers at racetracks, fairgrounds, stables, migrant worker

camps, and Civilian Conservation Corps, were chaotic and squalid.

Existing buildings, such as livestock stalls, were hastily cleaned

and used despite the remaining stench. Living quarters were supplemented

with temporary army barracks not designated for families with small

children or the elderly.

As you might expect, signs such as this were common in the days immediately

prior to reporting to these camps.... one of which was Minidoka

Relocation Center.

A few months later families were uprooted again, taken by bus, train,

and truck caravan under military escort to one of ten War Relocation

Authority centers.

Primary consideration for these "centers" was given to

isolated desert or swamp areas with railroad access and agricultural

potential.

Minidoka

Relocation Center is one of those centers.

Despite their internment, most Japanese Americans remained intensely

loyal to the United States, and many demonstrated their loyalty by

volunteering for military service. They were segregated into all Japanese

American combat and intelligence units commanded by non Japanese Americans.

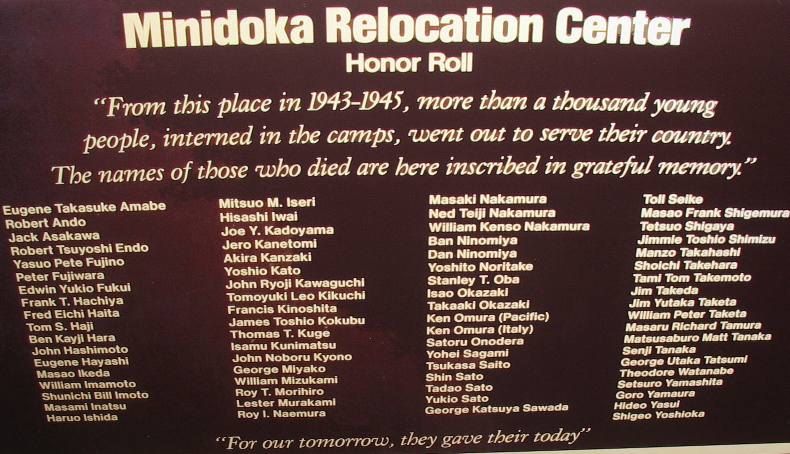

Of the ten relocation centers, Minidoka

had the highest number that served in the military, about 1,000 internees

-- nearly 10% of the camp's total population during its peak. The

442nd Regimental Combat Unit and the 100th Infantry Battalion were

two such units. The 442nd combat unit fought in France and Italy alongside

the 100th Infantry Battalion from Hawaii (also all Nikkei) and was

the most highly decorated unit of its size in American military history.

During WWII, 73 soldiers from Minikoka

died while fighting for their country and two received the Congressional

Medal of Honor.

Internment camps strove to be self-sufficient. The WRA (War Relocation

Authority) worried that prolonged idleness would deepen the internees'

feeling of frustration and isolation. Also, the war effort demanded

that all labor be used, and it was hoped that constructive work would

help rehabilitate internees in the eyes of their countrymen.

It was determined that WRA internee pay would not exceed the base

pay of a soldier, $21 a month. The adopted scale used was $12 for

unskilled labor, $16 for skilled labor and $19 for professional employees.

Concerning RELIGION, Camp policy was to allow complete freedom of

worship, except barring State Shinto on the grounds that it involved

Emperor worship. The Japanese language, banned from daily life, was

permitted during religious service.

A building--generally the recreation hall--was provided for services,

and internees were permitted to invite outside pastors if they wished.

The Minidoka

Relocation Center was a 33,000 acre site with over 600 buildings,

operational from August 1942 until October 1945. Administrated by

the War Relocation Authority, the total population was about 13,000

internees. They lived in barracks with communal bathrooms, showers,

laundry, and mess halls. While most rural American life styles were

austere by today's standards, living conditions at the Center were

harsh and internees endured extreme temperatures, no running water,

and a demoralizing lack of personal privacy.

Each barracks at the Minidok

Relocation Center was about 20 by 100 feet long, divided into

four or six rooms, each 20 feet wide by 16 to 25 feet long. A single

hanging light bulb, cots for sleeping, and a potbellied stove were

the only furnishings. Several internees later recall "foraging

for bits of wallboard and wood"; scrounging for materials to

build simple shelves and furniture.

Food was institutional and unfamiliar. Internees cleared and cultivated

over 900 acres of land, becoming almost a self-sustaining community

complete with vegetable gardens and hog and chicken farms. An astonishing

7,300,000 pounds of food was harvested in 1944. Working outside of

the camp, the internees were also an indispensable source of labor

for southern Idaho's agricultural-based economy.

Despite the harsh living conditions and gloomy circumstances, internees

were resourceful. They adapted to the desert environment in many ways,

creating beauty in the bleak landscape, defining pathways with decorative

stones, and constructing traditional Japanese gardens and flower gardens.

Some of those features still remain visible today - yet most traces

of daily life at Minidoka

are now gone. Frankly, I didn't see anything other than two unidentifiable

stone structures.

Relocation Centers such as Minidoka

were subject to the same commodities rationing as the rest of the

country. Victory Gardens supplemented the rations and internee crews

recycled fats, metal, and other material considered vital to the war

effort.

The physical surroundings, while not having s profound an impact

as the political and philosophical issues, had a great effect on family

life. Internees arriving at the camps found identical blocks of flimsy

poorly build barracks.

They quickly improved and personalized their new lodgings, first

to make them habitable, and later to make them into homes. The physical

changes made were important ways of taking control over their own

lives. The changes also helped personalize the identical barracks,

and to help relieve the monotony.

Many of the Nisei (1st Generation) tried to treat the entire experience

as an adventure or merely a temporary setback. Often one major goal

was to find ways to prove their loyalty to the outside world.

To the Japanese education was a high priority but adverse conditions

took their toll. Many internees believed that the deficiencies in

the educational program they received handicapped them. Children's

attitudes towards the half free, half prison world of the centers

discolored their attitudes about education.

Since E.O. 9066 was issued, the Federal Government has recognized

that incarceration and internment, based solely on ethnic status,

is a violation of the U. S. Constitution and that American citizens,

because they were of Japanese ancestry, were denied due process of

law.

1948 The Japanese American Claims Act of 1948 was a law intended

as recourse for financial losses for real property. Some 23,000 claims

totaling $131 million were filed. The final claim wasn't settled until

1965 and Congress had only appropriated a total of $38 million.

1976 Executive Order 9066 Repealed.

On its 34th anniversary Executive Order 9066 was formerly rescinded

by President Gerald R. Ford.

1980 President Jimmy Carter commissioned a study to determine the

causes of the actions that lead to internment. (Commission on Wartime

Relocation and Internment of Civilians) Their official findings concluded:

* "...Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity..."

* "...causes that shaped these decisions were race prejudice,

war hysteria and a failure of political leadership."

1988 Civil Rights Act of 1988. Signed by President Ronald W. Reagan,

this law authorized the payment of $20,000 to each living internee.

1992 Civil Rights Act Amendments of 1991. Signed by President George

Bush, this law appropriated additional funds for redress and provided

an apology for the government's actions.

That's it folks. I do not know where you can obtain more information

about this monument unless you get it from the National Park Service.

Keep in mind that the monument is newly authorized and there are

virtually no amenities such as water at the site. (I saw a port-a-pottie)

This is all there is --------- no signs, no nothing. But this is

the site of the Minidoka

Relocation Center.

Realize that there are no directional signs to help you find your

way to the site. You will have to contact a Ranger at Hagerman

Fossil Beds National Monument for information. However, you can find

all there is to the Minidoka

Relocation Center National Monument by following these directions:

Find your way to downtown Eden (small community 15-miles northeast

of Twin Falls). Turn north on Idaho Street (also called South Eden

Road) and go 5.8 miles to Hunt Road then turn left (west) and drive

another 2.2 miles. What there is of the monument is two stone structures

at the corner of Hunt Road and the irrigation canal bridge. N42°

40.666 W114° 15.061is the Lat/Lon.

Warning: There are several different sets of directions floating

around on the internet and other places. Some of these directions

are off by over 50-miles. Be aware that you likely are on a "wild-goose-chase"

on any directions other than these. Ask me how I know.

Until next time remember how good life is.

Mike & Joyce Hendrix

Mike

& Joyce Hendrix who we are

We hope you liked this page. If you do you might be interested in

some of our other Travel Adventures:

Mike & Joyce Hendrix's home

page

Travel Adventures

by Year ** Travel

Adventures by State ** Plants

** Marine-Boats

** Geology ** Exciting

Drives ** Cute Signs

** RV

Subjects ** Miscellaneous

Subjects

We would love to hear from you......just put "info" in

the place of "FAKE" in this address: FAKE@travellogs.us

Until next time remember how good life is.