Golden Spike National Historic Site at Promnatory,

Utah

May 31, 2007.

This morning we visited Brigham City,

Utah & the Bear

River National Migratory Bird Refuge. We dropped the motorhome at a Super

Wal Mart located at exit 364 and headed to Bear

River National Migratory Bird Refuge 20-miles west of Brigham City, then

to the Golden Spike National

Historic Site at Promnatory, Utah.

To get to the Golden

Spike National Historic Site from I-15 take exit 368 and travel west on

SR 13 to the intersection with SR 83. Continue west on SR-83 for around 25-miles

following the brown signs.

Keep in mind that this is the FIRST part of a two-part

series covering the Golden Spike

National Historic Site. Do not forget to view the second one: Golden

Spike NHS part-2

While

America's first railroads were operating in the 1830s people of vision foresaw

transcontinental travel by rail. This idea gained support as a national RR system

took shape.

By the beginning of the Civil War, America's eastern states

were linked by 31,000 miles of rail, more than in all of Europe. Virtually none

of this network, however, served the area west of the Missouri River.

Until

the Great American Desert and the Rockies were bridged, the vast western territories

would be a part of the nation in name only. A continent-spanning railroad would

also bring more tangible benefits: It would boost trade, shorten emigrants' journey,

and help the army control American Indians who were opposed to white settlement.

Anticipating great financial and political rewards, northern, midwestern, and

southern senators made their cases for locating the eastern terminus in their

regions.

In California, Theodore Judah had his own plan for a transcontinental

railroad. By 1862 the young engineer had surveyed a route over the Sierra Nevada

and persuaded wealthy Sacramento merchants to form the Central Pacific RR. That

year Congress authorized the Central Pacific to build a railroad eastward from

Sacramento and in the same act chartered the Union Pacific RR in New York. The

Civil War had removed the southern senators from the debate over the eastern terminus

location, thus the central route near the Mormon Trail was chosen, with Omaha

as the eastern terminus. Each RR received loan subsidies of $16,000 to $48,000

per-mile, depending on the difficulty of the terrain, and 10 land sections for

each mile of track laid. While work was started in 1863 not much was accomplished

while the country's attention was diverted by the Civil War. Investors could reap

greater profits from the war, and the army had first priority on labor and materials.

Central Pacific's Collis Huntington and UP's Thomas Durant, exemplars of the no-holes-barred

business ethics of the period, visited Washington with enough cash to help congressmen

understand their problems. A second RR Act of 1864 doubled the land subsidies.

Still little track was laid until labor and supplies were freed at war's end.

Central

Pacific crews faced the rugged Sierra range almost immediately. While the Union

Pacific started on easier terrain, its work parties were raided by Sioux and Cheyenne.

With eight flatcars of material needed for each mile of track, supplies were a

logistical nightmare for both RRs, especially Central Pacific, which had to ship

every rail, spike, and locomotive 15,000 miles around Cape Horn. Both pushed ahead

faster than anyone had expected. The work teams, often headed by ex-army officers,

were drilled until they could lay two to five miles of track a day on flat land.

Union

Pacific drew on the vast pool of America's unemployed: Irish, German and Italian

immigrants, Civil War veterans from both sides, ex-slaves, and even American Indians

--8,000 to 10,000 workers in all. It was a volatile mixture, and drunken bloodshed

was common in the "Hell-on-wheels" towns thrown up near the base camps.

Because California's labor pool had been drained by the rush for gold, followed

by the silver boom, Central Pacific hired several thousand Chinese, the backbone

of the railroad's work force.

By mid-1868 Central Pacific crews had crossed

the Sierra and laid 200 miles of track, and the Union Pacific had laid 700 miles

over the plains. As the two work forces neared each other in Utah, they raced

to grade more miles and claim more land subsidies. Both pushed so far beyond their

railheads that they passed each other, and for more than 200 miles competing graders

advanced in opposite directions on parallel grades.

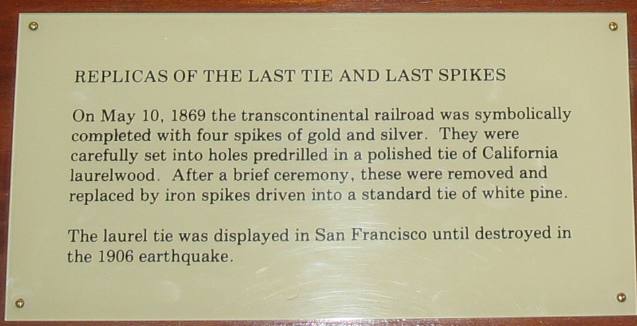

Congress finally declared

the meeting place to be Promontory Summit, where, on May 10, 1869, two locomotives

pulled up to the one-rail gap left in the track. After a golden spike was symbolically

tapped, a final iron spike was driven to connect the railroads. The Central Pacific

laid 690 miles of track; the Union Pacific 1,086. they had crossed 1,776 miles

of desert, rivers, and mountains to bind together East and West.

Thus, the

transformation of the western United States was wrought by two rails four feet

eight and one-half inches apart, snaking across hundreds of miles of sparseness.

They joined two oceans and cemented the political union of states with a physical

link.

It also was a wedge through the frontier. The west at that time belonged

to the American Indians and the enourmous herds of buffalo on which they depended.

Many Indians fought white settlement of their land, but as the railroads brought

in car after car of troops and supplies, the Indians could no longer repel the

army. Settlers flowed in behind and put the land to the plow, while millions of

buffalo were killed.

For the late emigrants, the railroad changed what

it meant to be a pioneer. A journey that had taken six months by ox-drawn wagon

took six or seven days by train. The Union Pacific built railroad stations along

the way, and settlements grew up around them. Some railways sold supplies and

even provided dormatories for emigrants until they could settle. Twenty-one years

after the railroad was completed, the frontier was history.

Even before

it was completed, the railroad had begun to change the West. As the railheads

moved across the land, supply houses and service businesses grew up in their wakes.

Some tent towns like Reno and Cheyenne survived to become respectable cities.

Workers who had been trained on the railroad built towns and staffed factories

and mines.

Another anticipated benefit of the railroad, increased trade

with the Far East--never materialized. The Suez Canal was completed the same year

as the railroad, and Far East goods could now be shipped to Europe faster by way

of the canal than across America. But that loss was compensated for by the rapidly

growing western rail trade, out of which a vigorous, interlocking economy developed.

Western mountains were rich with low-grade silver, lead, and copper ores, made

profitable by long trains of ore cars. They were used by industries in the East,

whose products found a growing market in the West. Western agriculture made geat

advances as new farming techniques, livestock strains, and machinery moved in

by rail. Cash, generated by produce shipped east, poured into the region, and

budding western financiers learned how to raise money to capitalize new industry.

Factories were built, and the growing industrial population provided a new market

for western farm produce.

More than economically, the railroads tied the

West to the eastern states. They altered the very pace of life, putting people

on a schedule who had always geared their activities to natural rhythms. National

politics came west, as candidates made whistle stop tours of small towns in search

of votes. As railroads made travel into the West safe and comfortable, visitors

from the eastern states and Europe toured the "New America".

With

the coming of the railroads, the West, for so long the vast, forbidding "out

there," was brought into the national life.

That folks, pretty much

sums up the signifigance of this Golden Spike Historical Site. It is the place

where the last spike spanning the continent was driven changing forever life across

this country.

The

Visitors Center has on display two recreated icons of railroading history at the

Last Spike Site. Central Pacific's Jupiter and Union Pacific's No 119 steam out

and perform for visitors on most days, weater permitting.

This is Union Pacific's Steam Engine 119 performing for visitors.

Inside

the Visitors Center a museum has exhibits of tools and equipment used to build

the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Also a short video tells the story of the

great race to Promontory.

In addition to tools and equipment a section

is reserved for displaying memorabelia connected with this momentus event.

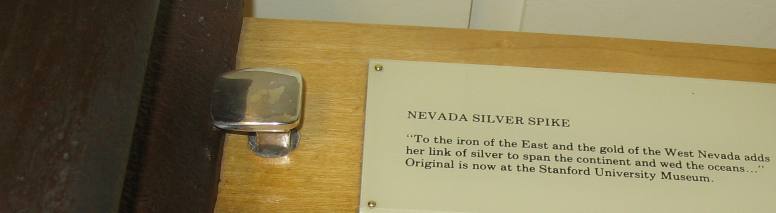

It

seems there was more than one gold spike. In addition there was several silver

spikes, and other spikes that were a combination of gold, silver and steel.

In my opinion this is one historic

place that everyone should visit. Not for the spectacular scenery but to experience

first hand the awesome achievement this site commemorates.

Until next time remember how good

life is.

Mike

& Joyce Hendrix

Until next time remember how good life

is.

Mike

& Joyce Hendrix who we are

We

hope you liked this page. If you do you might be interested in some of our other

Travel Adventures:

Mike & Joyce Hendrix's

home page

Travel

Adventures by Year ** Travel

Adventures by State ** Plants **

Marine-Boats ** Geology

** Exciting Drives ** Cute

Signs ** RV

Subjects ** Miscellaneous

Subjects

We

would love to hear from you......just put "info" in the place of "FAKE"

in this address: FAKE@travellogs.us

Until next time remember how good life

is.